Scott, Wong and Gunn, The Poetics of Sex

Writing in The Poetics of

Space, Bachelard discusses box-like spaces in terms of intimacy and security.

Locked boxes represent hiding, are protected hermetic spaces. Though they are

never absolutely safe, he remarks, because they can be threatened by extreme

violence. (And it should be added: guile). These thoughts echo around the

toilets in gay poetry, not in quite the way that Bachelard would have seen. But

yes, cubicles, from the Latin “to lie down”, are confined spaces, like shells,

that open up to a world beyond their smallness— they have an interior life that

is separate from the outside. Also, they are places open to police entrapment

and surveillance.

The confined space of the toilet-box, as Marc Siegel has argued (in relation to a 2017 art exhibition in Berlin that featured

men and urinals) is a synecdoche for the

closet, for the shame in which gay men seal themselves away with forbidden

desires. The Pissbudenschwulen, cottagers or tea-room users, are viewed in German gay culture as the lowest level in the gay sexual

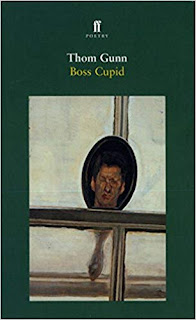

hierarchy. Three very different poems by Thom Gunn (The Passages of Joy, 1982),

Nicholas Wong, (Crevasse, 2015) and Richard Scott (Soho, 2018) reveal different

visions of the toilet/closet. Reading them chronologically, but in reverse, is

interesting, in terms of what they say about gay “identity” and how they

operate as poems.

Public Toilets in Regents Park.

The men hear are bird footed

feathering past the attendant’s

two-way mirror

unperturbed by the colonising

micro-organisms

bulleidia cohetia shigellosis

Scott’s “bird footed” dehumanises

the cottaging men from the onset and the meaning isn’t exactly clear. Is the

reader to imagine them as web-footed and adapted for puddles of water? Or does

Scott mean that they resemble dinosaurs? The term “bird footed” usually appears

in Paleontology. The gay men blur as they pass the spying mirror, if we read

“feathering” in a technological way. As is typical with Scott, the poetry moves

excitedly with thematic metaphors and there is a tendency to word-play rather than fix a real scene: “feathering” is

looking towards the end of the poem where gay men have idiomatically feathered

their nest. In lines 3-4 there is a switch to a medical register and

“colonising” indicates that the men are not in control— are subject to disease's colonial

rule and infection.

Stanza 2 develops this theme: this

is a place where the “fist deep” pool” in the u-bend and the activities on

offer produce a risk of venereal infection. Of course, Scott intends the

sexual-pun on “fist-deep” and “fisting”, but is the cleverness appropriate

here? Fisting is not an activity usually associated with cottagers, those on the borders of gay

sex, nor is it likely in a small cubicle. The iconography of cottaging centres on the glory hole. Here, again, Scott is playing with images rather than imagining

the psychology of the scene. The men are cyphers in a language game.

Compare this with Wong:

Self-portrait as a Cubicle.

Keep me clean—

that microbial oval toilet seat,

over-used, turned

ivory with occasional drips

of yellow

a Jackson Pollock

on periphery.

Literally, Wong provides a ground

perspective. In a state of metamorphosis he has become the cubicle. He seats

himself objectively outside the act. The poem fulfils the next stanza:

Keep me sanitized

The poetry is cleaned up. Superfluous

words are removed. And it cleverly reverses Duchamp’s art process. His infamous

readymade, Fountain 1917, became a work of art because of how he saw it.

Here,

the cubicle claims art as its own. The poem turns craftily on “drips/of

yellow.” The “drip” paintings of Pollock are conjured up and the toilet signs

itself as a work of art. At the closing of the poem, the cubicle is animated

into a human participant. By removing himself to an object outside of himself,

Wong depicts not only the isolation that comes with being gay but also the

alienation that comes with writing his experiences, especially intimate sexual one, in a colonial language.

These poems show two very

different views of sexualised cubicles. Thom Gunn’s version of the

closet/toilet is written from an entirely human perspective. His poem is an

impulsive and known encounter, rather than an improvised and anonymous one. By

setting it within dialogue, as a story being told, Gunn preserves an intimacy

between two men and draws a reader into the poem as a third party.

The Miracle.

“Right to the end, that man, he

was so hot,

That driving to the airport we

stopped off

At some McDonald’s and do you know

what,

We did it there. He couldn’t get

enough.”

— There at the counter? — “No, that’s public stuff

‘There in the rest room. He pulled

down his fly,

And through his shirt I felt him

warm and trim.

I squeezed his nipples and began

to cry

At losing this my miracle… [“.]

This poem is model Gunn. Iambic

pentameter is loosened into memorable

speech and exact casual rhymes create a bound experience. Within traditional

form, unorthodox subject matter is gradually exposed. And the eye is firmly on

sensation, especially touch, as language moves towards a spiritual,

psychological boundary— “my miracle”.

How far a poem can travel in a

short space of time is often a test of quality. By the close of Scott’s poem, a

reader has moved through some rather forced ornithological metaphors, “a

beautiful cock unfolding like a swan’s neck”, heard “gasps of contact…inside

each nested cubicle” (do toilet cubicles nest inside one another like living

room coffee tables or storage boxes?), to the point where the sexual occupants

“disperse as mallards from the face of a pond”. The termination of the poem is appropriate, it does portray how the cottaging males escape quickly and return to

their natural environment. They merge once again into their parkland habitat.

But the poem has done nothing new: it has described cottaging in lurid detail,

as a locus of shame, and that is it.

Wong’s poem concludes by drawing

together a variety of eyes. The art object views the eye peering through a hole

in its body and beholds the human in the next cubicle as a lover of beauty: it

sees in its artistic terms.

You peep

through it, a fecund

kaleidoscope

for a face—

less prepuce

cordoned off by me.

Kaleidoscope etymologically is

made from “beauty” and “form”, though “scope” suggests seeing and visual form.

The words rotate as a kaleidoscope does. A reader sees (with the cubicle) an

eye gazing through the hole. The adjective “fecund” suggests intellectual/aesthetic

productivity, exactly what the lavatorial art object would perceive. The “face”

in the next cubicle is reduced to its hole, but the existence of a face is

acknowledged. A further reduction occurs as “face” becomes “faceless prepuce” and a penis obliterates the

human: the man is nothing except his penis. The poem ends by observing with a

sense of wonder and vision whilst recognising that the sexual act is

“cordoned”, restricted by the wall of the cubicle, and also, if we think of

“cordoned” as a line of bodies or a rope marking off a prohibited scene, an act

that is policed by the cubicle and by society. This is a fine example of

concision— a lot is covered in a few lines.

At the close of “The Miracle”, a miraculous

love is symbolised by a stain that is left on one of the men’s boots as a result of sex. This

leads to:

— “Snail track?” – Yes there.” – “That was six months

ago.

How can it still be there?” – “My

friend, at night

I make it shine again, I love him

so,

Like they renew a saint’s blood

out of sight.

But we’re not Catholic, see, so

it’s all right.”

Gunn’s Hardyesque poem, based on

an anecdote told to him, converts the anonymity of the corporate bathroom into

a scene for corporeal desire and wonder-working: the lover becomes a pilgrim

who keeps his holy artefact in great shape by artifice. The poem is told with

wit and human sensitivity, and inserts American gay sex (provocatively) into

established English traditionalism. This poem bends Hardy, as does the epigraph

at the start of Boss Cupid (2010): “… a cool, queer tale.”

Scott, Wong and Gunn are three

poets of the body, but they have very different perspectives on being gay. These

three poems from three countries and three continents— the UK, Hong Kong and the

USA, Europe, Asia and North America— record Klappensex with distinctive and

challenging perspectives.

Comments