Marechera: My name...is mind.

The writer Dambudzo Marechera was born in Zimbabwe, 1952, and died in Zimbabwe, 1987. His life, as a novelist and poet, was a life spent in opposition, his poetry emerging as an unfamiliar collection of straight-forward and hermetical images, his death occurring as a mystery: he died from the terrible cryptogram AIDS, a disease that was still being named and one that continues to be nameless in much of Africa; also from what appeared to be a sustained assault. Soyinka has described Marechera as a “profound if exaggeratedly self-aware writer”. And that phrase depicts what Marechera was opposed to, as a writer and an activist—as a human being. He argued that Africa had a place for depth, but was so steeped in tradition that anyone with a self and personal life automatically became an outsider .

Marechera’s biography is undoubtedly one of extremes. He was expelled from the University of Rhodesia because of how it rigorously carried through racist practices. This was followed by a further expulsion from the University of Oxford because his behaviour was deemed disturbed. Or as Marechera saw it: expulsion from an instititution that lacked intellectial rigour. Commenting upon Marechera’s short story, “Oxford, Black Oxford”, the astute novelist Helon Habila, offers a peculiar apologetic tone: “The brand of racism… was almost polite”. How that statement shows the divide at work here! Actually, what Marechera reflects in “Oxford Black Oxford” is the institutionalised (class based) racism that the United Kingdom has been able to deny until quite recently. Perhaps, its intolerance is not as noticeable as apartheid, not as prejudiced as what Marechera was to later encounter in the country of his birth, but it is neither “polite” nor some sort of benign cancer. The racism that Marechera comments on became the root of the racial politics that Thatcher’s government was laying down from 1976-82. In 1982, Marechera returned to Zimbabwe. A disastrous move for someone who believed in self-criticism and state-criticism, whose free-thinking poetry denied boundaries and any form of censorship. Not surprisingly, with Mugabe as Prime Minister, Marechera became an enemy of the state. He was beaten up, arrested in 1983 before the International Book Fair as a threat to national security and his literary agency was closed down after state pressure.

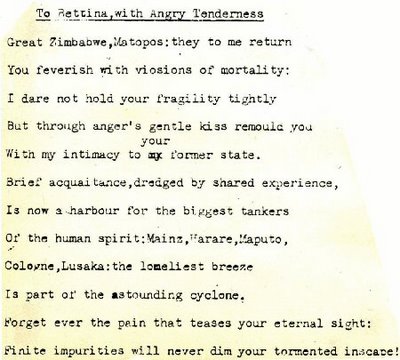

For Marechera, the word “international” always came before the word “national”. And his poetry is a testament to this belief, for it borrows widely and refuses to be limited by any kind of Africanism. It is also a poetry which sweeps aside one of the main tenets of modernism, Eliot’s “objective correlative”. Words, as Marechera pointed out in a reflective 1984 interview, do not always correspond with feeling and when you are writing in English, as an international poet, you often have to rip its insides out to say what you want to say. It is this recognition that produces an irregularity in Marechera’s work. To excuse his poetry as “experimental” (i.e. being formed rather than formed, pre-maturity) is to miss the point. It is experiential and totally opposed to the nice rhythm and diction of what passes for English Modernism. This can be sensed in this type-script of “Angry Tenderness”.

The poem is a sustained oxymoron from start to finish. And just when the poem appears to be settled and understood in the mind, Marechera places “inscape”. From Hopkins, he borrows a poetic term that implies ordered, objective uniqueness. A most English notion is thrust into the heart of Africa and the reader is left, like Marechera, in a state of dizziness as “tormented inscape” rips up any sense of subjective conclusion. So much of Marechera is about demonstrating what the racist denies: the Black individual has a mind and can create a poetry about mind that challenges a white supremacist poetics.

The poems of Marechera were gathered after his death into a Collected Poems. The rightly titled Cemetery of Mind is a brilliant work of scholarship. Regrettably, it cannot do what is expected of a Collected Poems, give a chronology and a sense of development. But in a way that is as it should be because if there was any poet who hated the traditional notion of single-minded development and ordered poetic life, it had to be Marechera. In his poem, “Mind in Residence”, which puns on Writer in Residence, a role which he occupied at the University of Sheffield, in 1979, Marachera offers a poem of multiple perspectives. In the final six lines of the poem, the reader, who stands beside Marechera, looking down from that city of concrete balconies, waits for one word, “I”. It never comes and the final lines cannot settle down into grammatical closure. The poem is a symbol of Marechera’s poetic life. It cannot be sentenced.

Mind in Residence.

On grey twilit balconies

In T-shirts and shirt sleeves

Each shrouded in preoccupied misty thoughts

The several pasts of my life

Wait for this and all other days to end.

Down in the streets, antlike thoughts

In rags and overalls

Leaning against the derelict buildings

Squatting on the cracked much-stained pavement

All looking up at those looking down

From the grey twilit balconies of hindsight.

Comments